Ruby and The Lost Crystals: Post-Mortem.

Game 3D Unreal Perforce Wwise SAE Group

Content

1. Introduction

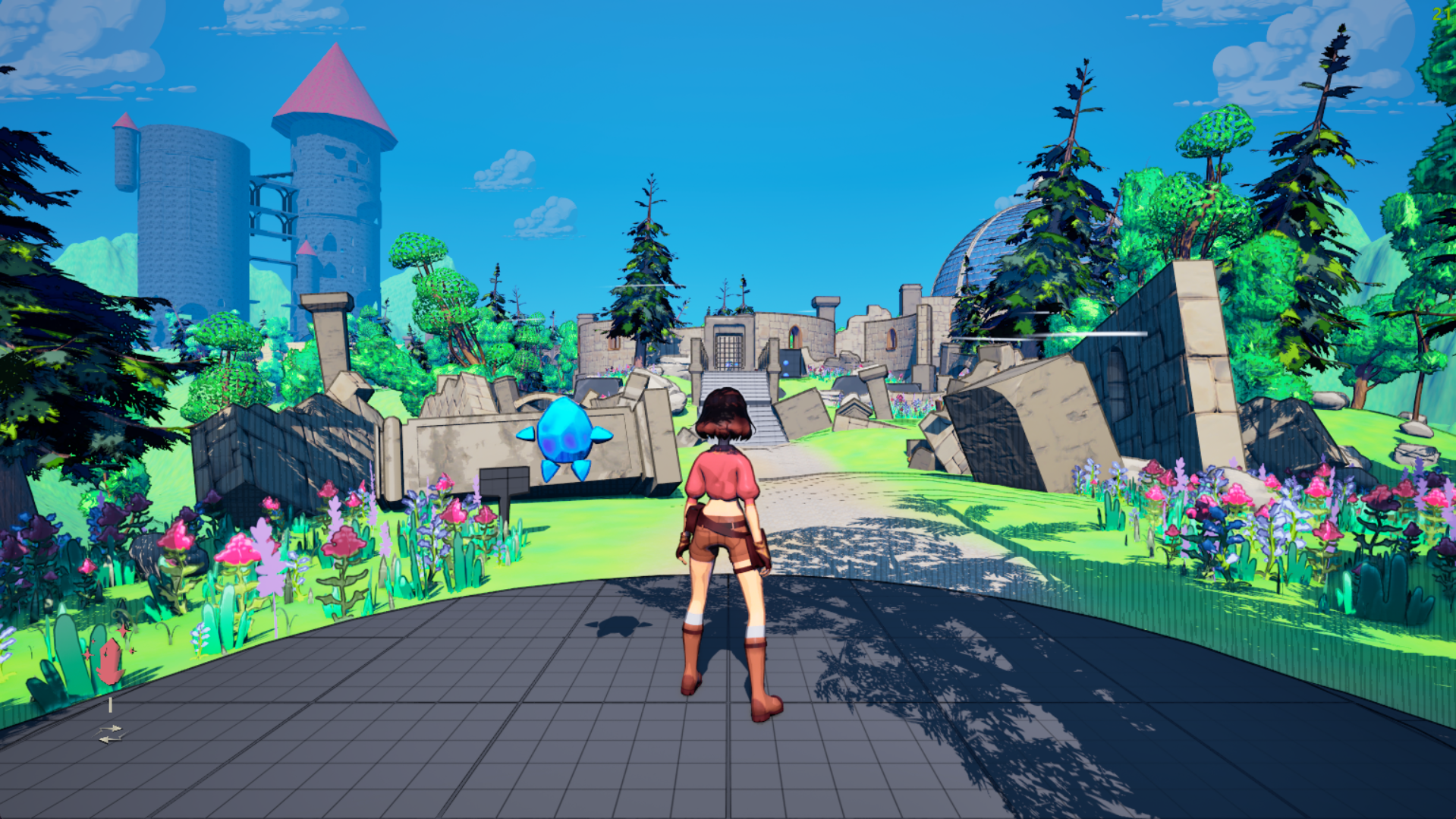

Ruby and the Lost Crystals is a third-year game project developed at SAE Institute Geneva, in collaboration with Game Programming, Game Art, and Audio Engineering students. The goal was to create a vertical slice in six months, providing a semi-professional experience where each discipline played a key role.

Set in a ruined fantasy world, the game follows Ruby and her companion Sapphire, who must work together to restore scattered crystals Ruby through physical interactions and Sapphire with magical projectiles.

2. Technical Report

As Lead Programmer, my role was to make the technical decisions for the project. I believe I made good choices regarding the Unreal tools we used, at least based on my knowledge at the time. However, looking back, I can now identify some technical implementations that did not work as expected, as well as Unreal features I was unfamiliar with that could have helped streamline the game’s development.

2.1 What worked well

In terms of organizing technical tasks, I think we managed well. We anticipated several issues before they occurred and made decisions accordingly. Additionally, we never encountered any checkout or versioning conflicts, which reflects solid code management within the team.

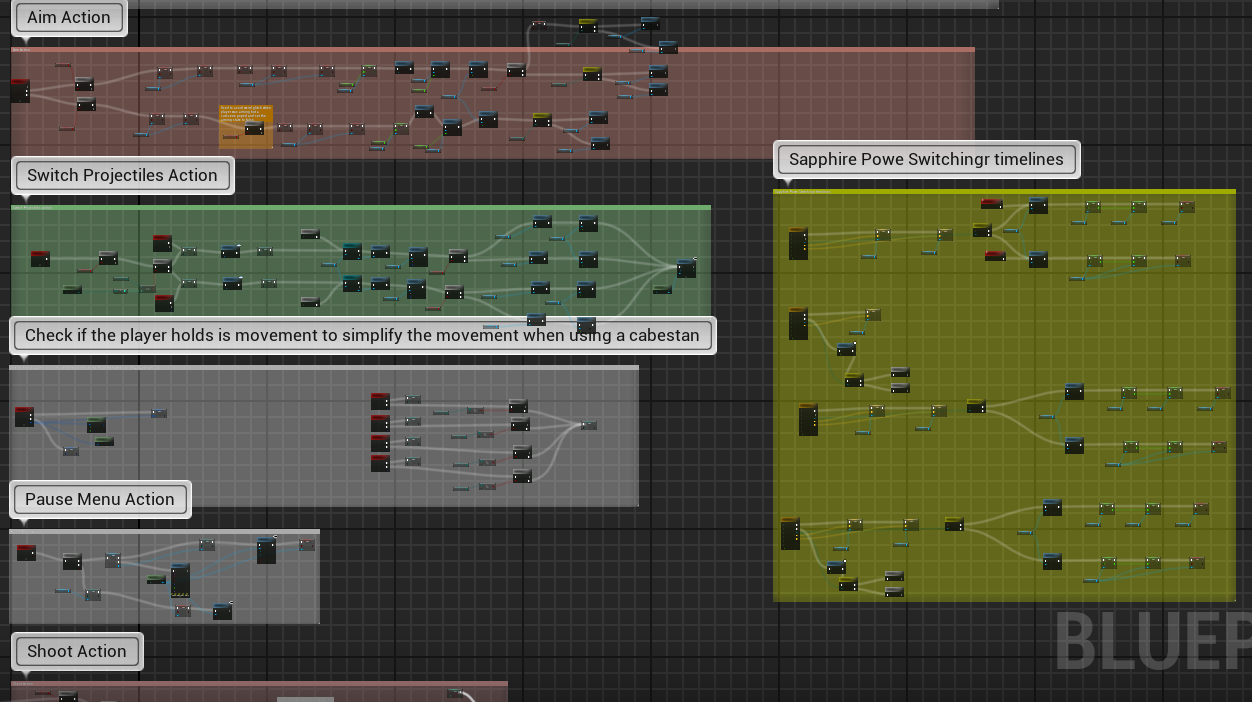

2.1.1 Blueprint Components: Modularity and Collaboration

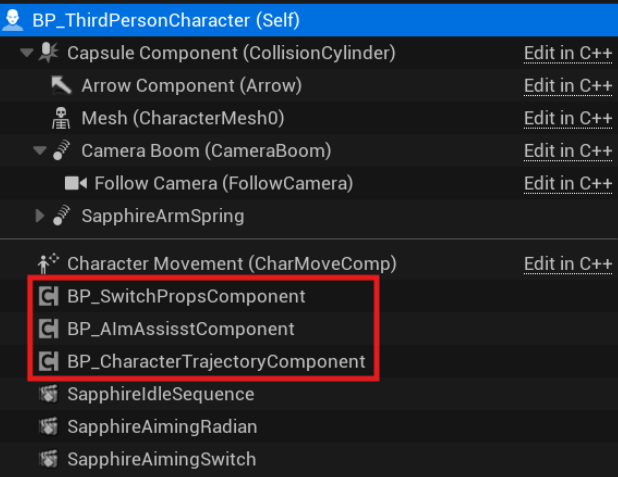

We chose to work with components whenever we had the chance, especially for the ThirdPersonCharacter code. This trick allowed us to separate the various player systems so that it was very easy to divide the code tasks between the programmers, avoiding checkout problems with perforce. Beyond the group work aspect, this solution also allowed us to avoid having huge unreadable files (although over time quite a few of them became unreadable).

Screenshot of the components of our ThirdPersonCharacter with our custom blueprint components highlighted in red.

2.1.2 Event Dispatcher: Avoiding Dependencies

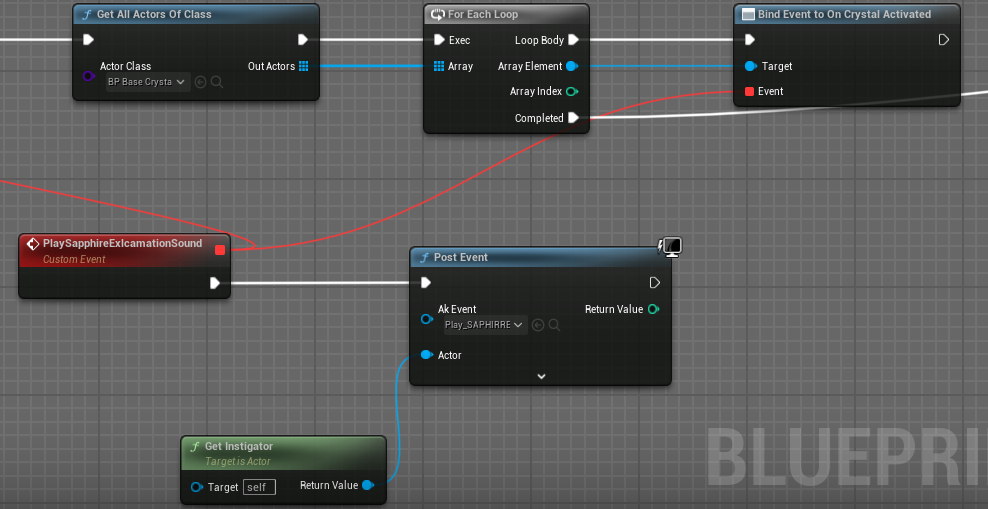

Another very useful programming technique was using Unreal’s Event Dispatcher. It allowed us to create events in an actor blueprint and have other actors subscribe to them, enabling a clean and modular communication system. For example, when the player lights up a crystal, we want a door to open, a sound effect to play, and characters to react. By subscribing each of these actors to the OnCrystalActivated event, we kept the logic separate within each actor while avoiding direct dependencies on the crystal, making the system more flexible and maintainable.

Example of a subscription to the OnCrystalActivated event from the ThirdPersonCharacter to play an exclamation sound for Sapphire when she unlocks a crystal.

2.1.3 Interfaces: Simplifying Behavior Management Across Interactive Objects

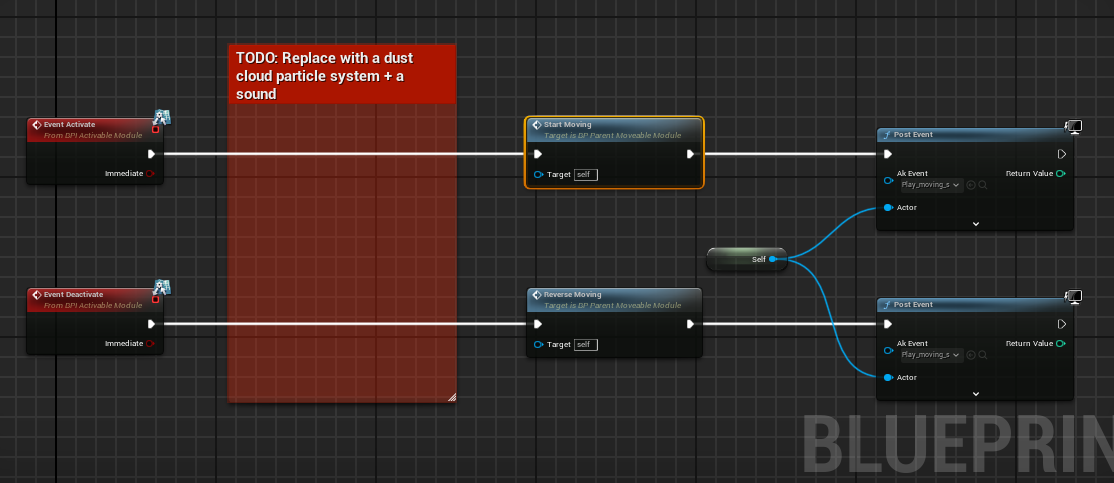

Another good practice we employed when programming the game was to use interfaces for actors with similar activation behaviors but different implementations. Since our game is a puzzle game with many interactive objects, we needed a flexible way to handle activations and deactivations. For instance, doors open and close, platforms move forward and backward, and so on.

To solve this, we created an interface called ActivableModule with an Activate and Deactivate functions. Any object that can be activated or deactivated simply inherits this interface and overrides the functions with its own specific behavior.

Example of using the Activate and Deactivate functions by a moving platform. You can also see a red comment that was used to anticipate areas of the code where something was missing. Here, we know we want to activate a VFX at this location, but since the VFX hasn’t been created yet, a comment is placed as a reminder and a guide for the future programmer.

This was just one example, as we used several other interfaces in the game to manage different behaviors across various objects. In addition to ensuring that the programmer overrides the methods of the interface, this approach also allowed us to have an object that could activate any other type of object. For example, we could create a button that opens/closes doors while also moving platforms forward/backward, without needing to store the doors and platforms in separate arrays.

2.1.4 Graphics Rendering: Simplifying Collaboration in a Stylized Workflow

From a graphics rendering perspective, choosing a physics-based cel shader was a great decision, as it simplified collaboration with the artists. Since this was our first time working with them, we wanted to align with their usual PBR (Physically Based Rendering) workflow rather than impose a new approach. As students, our goal was to avoid unnecessary complexity. If the cel shader had been too stylized, we would have required multiple iterations to refine the asset pipeline, something we lacked the time and experience to do within six months.

The Physically Based Cel Shader version for the final submission to the school on 14 February. Objects with low roughness have sharp color band transitions, while those with high roughness display smoother transitions.

2.2 Difficulties and Areas for Improvement

Some aspects of the project caused us to lose a lot of time, either due to a lack of knowledge of Unreal or a failure to anticipate certain problems.

2.2.1 Blueprint: Yes, but not too much

Choosing to develop the entire game in Blueprint was not the best decision. At first, we thought our gameplay mechanics wouldn’t be too complex, so using Blueprint seemed like a quick and easy solution. However, as the project progressed, our systems became more complicated, and the Blueprints became harder to read. We did our best to maintain clarity by adding comments and avoiding spaghetti code.

Screenshot of a part of the ThirdPersonCharacter Blueprint, showing our strategy of separating functionalities into blocks with comments.

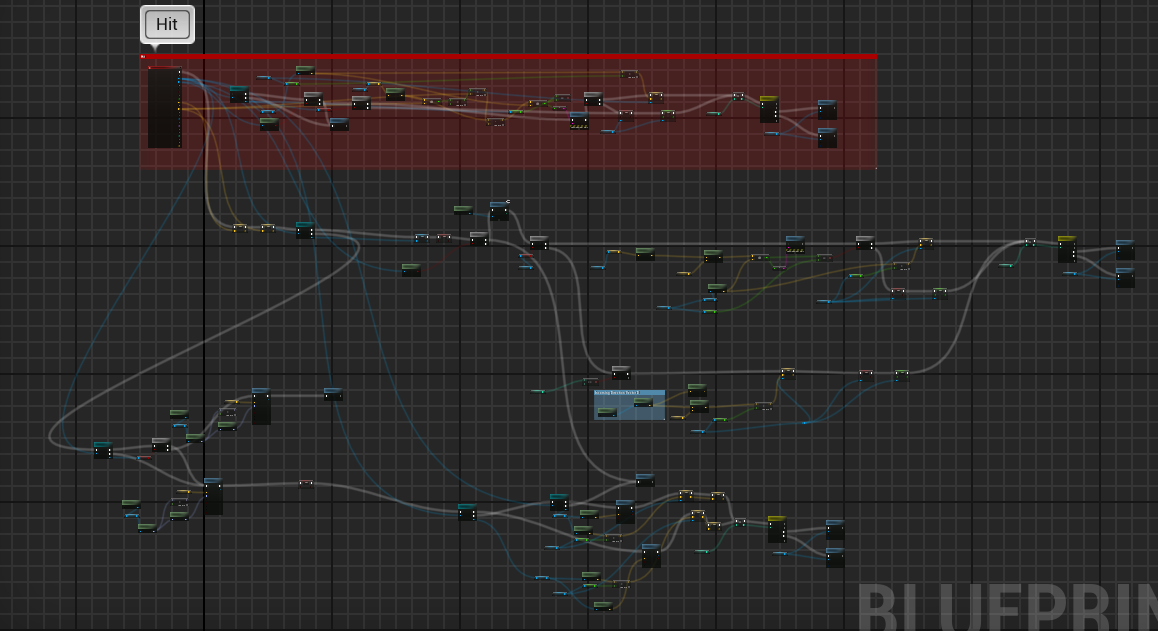

Unfortunately, the ease of prototyping in Blueprint often led us to forget about using functions or local variables, resulting in massive chains of nodes and wires. Additionally, we kept old code “just in case” the current version didn’t work properly. Combined with our fear of running out of time, which sometimes prevented us from refactoring, this resulted in labyrinthine structures of nodes and wires.

Screenshot of the Hit event for the projectile that illuminates crystals. The red-marked section shows old code that was left in place as a backup, demonstrating why this practice is a bad idea.

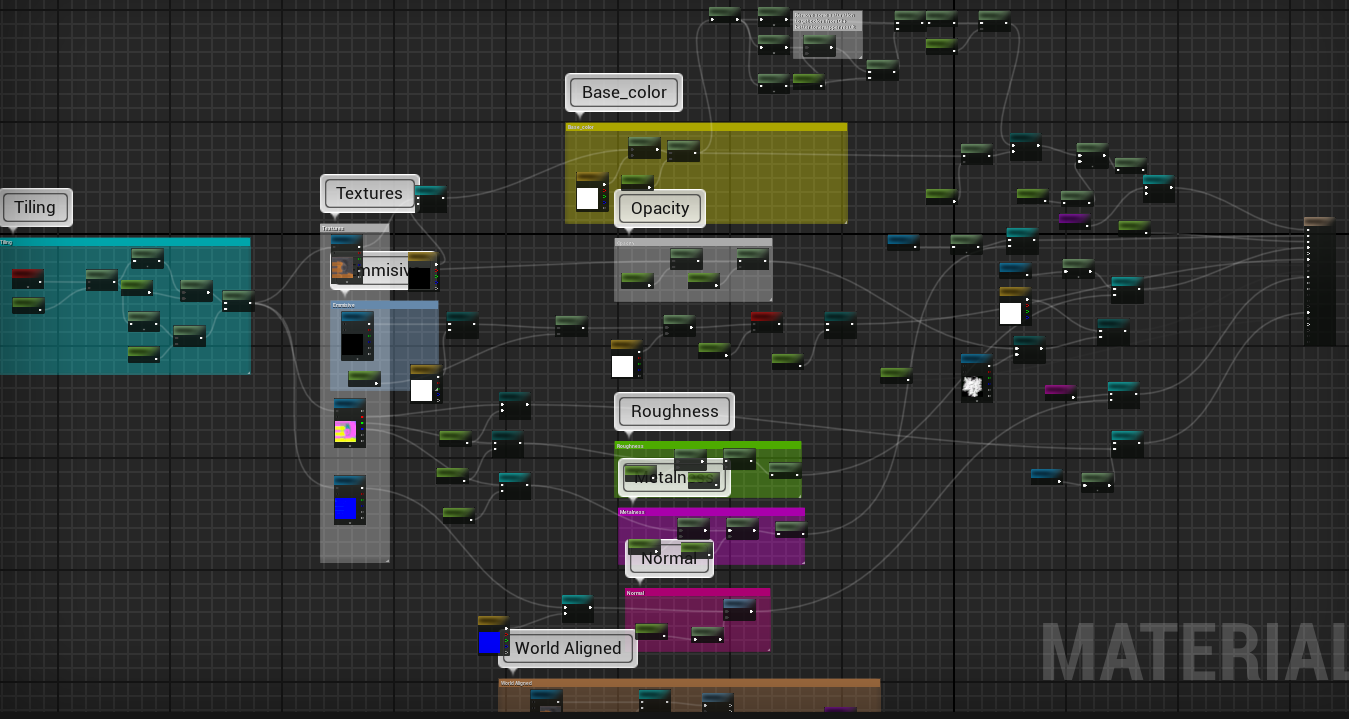

2.2.2 Materials: What I wish I had known from the start

Once the Game Artists joined the project, Isabelle, the Lead Game Artist, created a master material to allow tweaking parameters for each object in the game. Unfortunately, this material loaded between 5 and 8 textures, even when a material instance only needed a base color texture. This happened because the texture samplers had default textures, and no static switch parameters were used to prevent the shader from loading them. This issue significantly impacted our frame rate at one point in the project, and we only realized it late in development. When we finally modified the master material towards the end of the project, it broke many objects, requiring us to go back and fix them, which cost us a lot of time. As a Graphics Programmer, I now realize I should have reviewed the master material much earlier.

Regarding the master material, I also didn’t know that the blend mode of a material instance could be changed. Because of this, I duplicated the master material to create a separate masked master material for transparent objects. Once I realized my mistake, I deleted the duplicated material and had to manually reassign the correct material to many objects in the game.

Screenshot of the Master Material at the end of the project.

2.2.3 Game Builds: It’s never too early to make a build

Throughout development, we encountered several unpleasant surprises when building the game. The first major issue involved Wwise errors during the build process. Whether it was a missing .wav file, a checked-out file, or another issue, any Wwise error completely blocked us from building the game. The first time we encountered this was just a few days before an important meeting with Nicolas Brière. Fortunately, we managed to resolve the issues in time, but it caused significant stress.

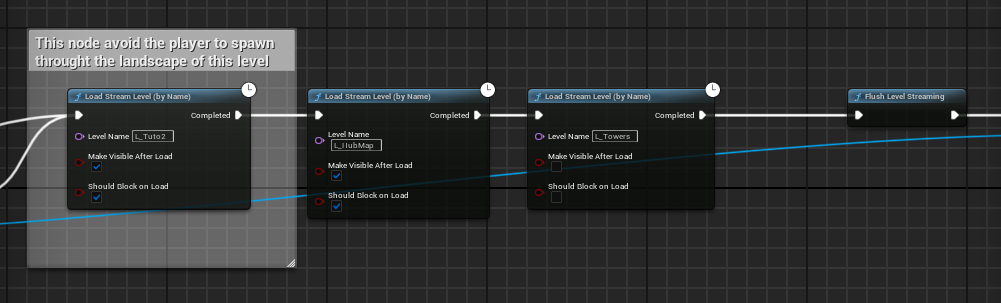

Another unexpected problem was the difference in behavior between the Unreal Engine editor and our game builds. Some systems that worked perfectly in the editor either malfunctioned or didn’t work at all in the final build. The most severe issue we faced was the player’s spawn behavior. In the build, the player spawned before any other objects, causing them to fall through the map indefinitely.

To fix this, we placed the PlayerStart actor in the persistent level (the parent level) and forced all sublevels to load, ensuring that the game wouldn’t start until everything was properly loaded. To this day, I don’t fully understand why this solution worked, as I didn’t have time to research the issue further.

Our method for ensuring that sublevels are loaded before the player spawns. These nodes are called in the Level Blueprint of the persistent level.

3. Teamwork Report

Teamwork played a crucial role in the success of our project. While we faced some challenges, I believe certain aspects of our collaboration worked particularly well. Below are the key elements that contributed to our effective teamwork, as well as areas that could be improved.

3.1 What worked well

Despite the organizational challenges of this project, we managed to implement effective work methods and tools. Here are the most notable examples.

3.1.1 Meetings Between Students

The first thing that comes to mind when thinking about what went well in our teamwork is our student meetings. I started them in early November after Nicolas Brière gave a kick-off session to encourage all students to engage more with the project. This kick-off made me realize that a team cannot function properly if we don’t meet in person at least once a week to review each other’s work, ask questions, and brainstorm.

These meetings led to many great ideas and increased collaboration opportunities between students from different fields. I consider our meetings one of the key elements that helped refocus everyone on the project and boost our productivity.

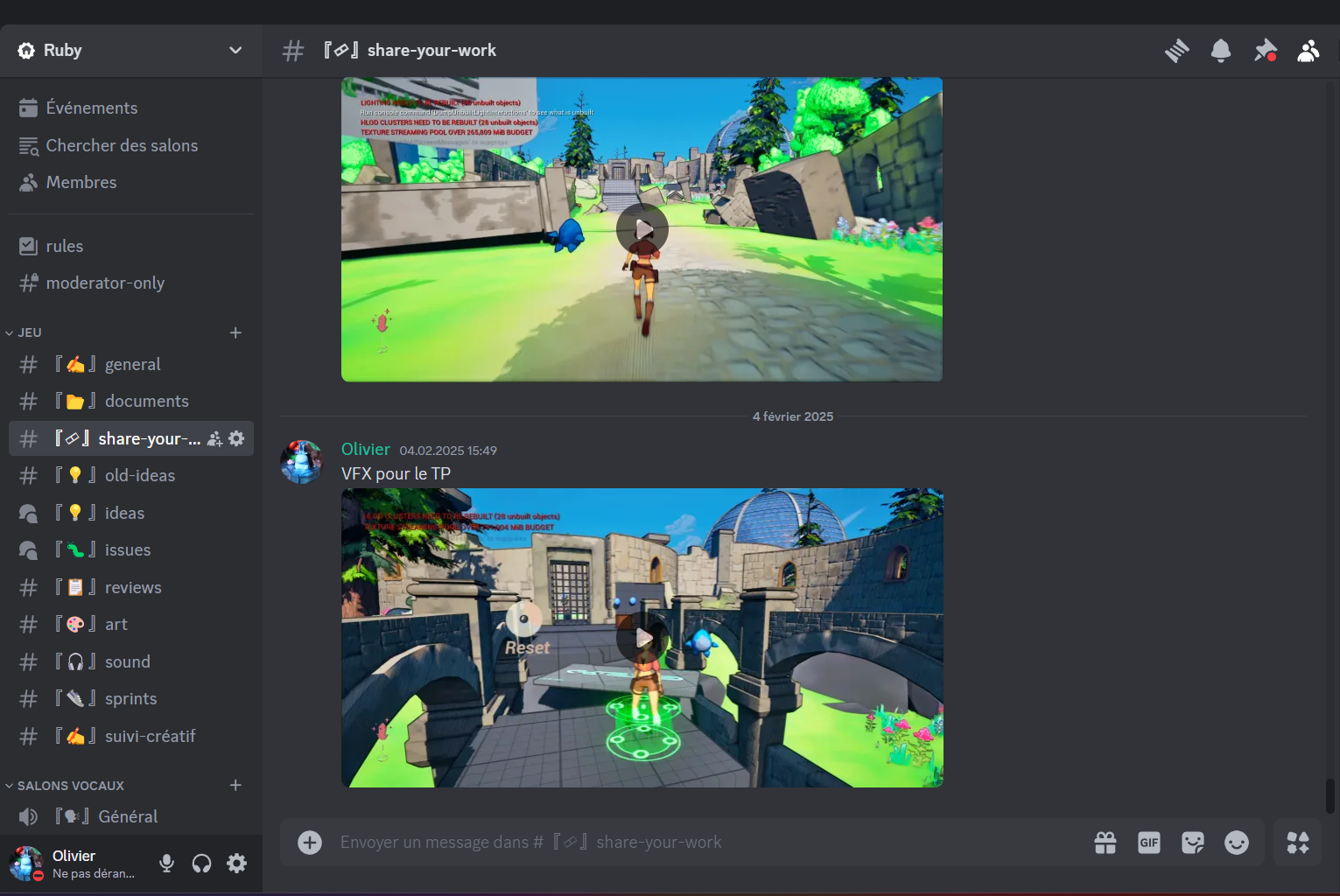

3.1.2 The Discord Server

Our Discord server was an excellent way to centralize everyone’s work and stay organized. All documents, visual assets, and sound files were accessible to everyone, allowing team members to view, modify, or use them as needed. Additionally, we had a dedicated channel where we posted progress updates, requested feedback, and asked questions. I believe this channel was a significant source of motivation, especially since we could track our progress from the beginning of the project.

In short, having a centralized space for discussions and file sharing helped us avoid scattering information across multiple platforms and ensured that everyone stayed up to date at all times.

Screenshot of our Discord server.

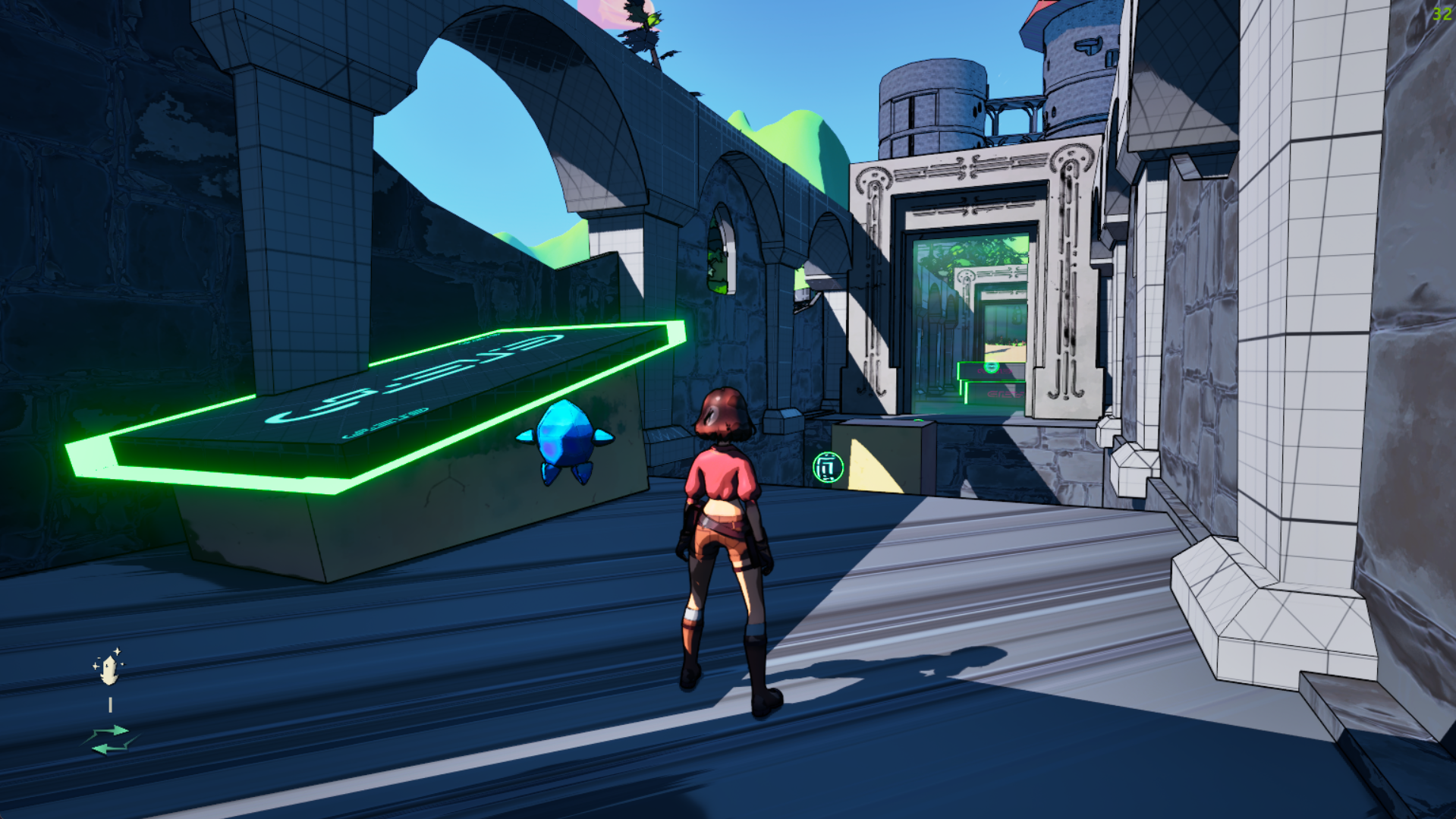

3.1.3 Helping Art and Audio Teams: Communicating Ideas Through Blockouts and Videos

The last element that I believe worked very well in our group work management was the effort we put into conceptualization to communicate our ideas to the Art and Audio teams. We didn’t just create a simple blockout of the game; we also made holes in the walls to visualize the ruins’ appearance, created numerous placeholders to provide a visual direction, and so on. This conceptualization effort greatly helped the Art team in designing their assets.

Screenshot of our blockout where you can see arches, broken walls and place holder materials.

For the Audio team, we recorded gameplay videos so they could see objects and the player in action to think about the necessary sounds for the game. The time we invested in making videos and a detailed blockout, along with the game references we shared, undoubtedly saved us a lot of communication time throughout the project.

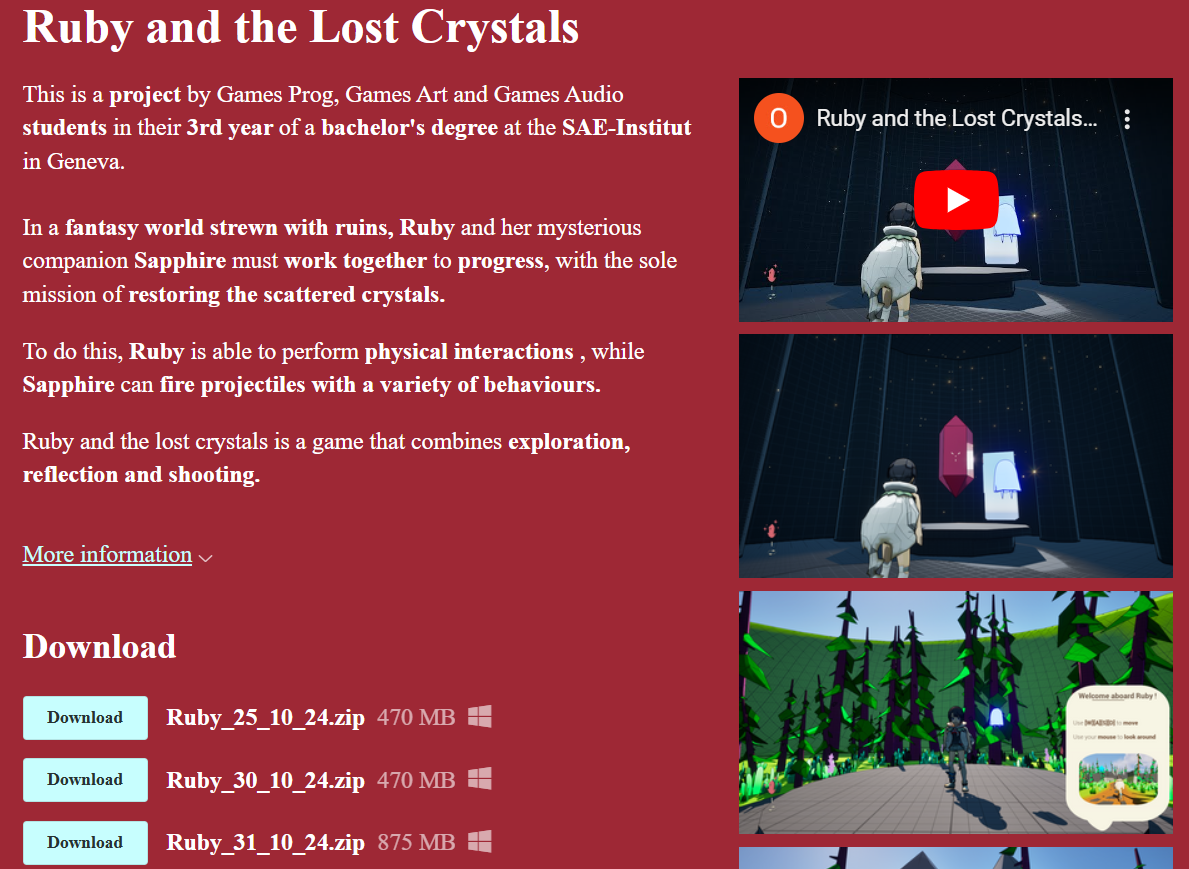

Screenshot of our game's Itch.io page, where we provided a gameplay video, screenshots, and downloadable builds of the game.

3.2 Difficulties and Areas for Improvement

Of course, not everything was perfect. We sometimes struggled to communicate our ideas effectively, and our priorities were not always set correctly.

3.2.1 Agile Methodology: Perhaps Too Much.

We decided to use the Agile methodology to manage our project. We conducted sprints of two to three weeks and adjusted our objectives based on the results of each sprint. The problem was that we became too lenient and fell behind because we didn’t have strict deadlines. The Art team, in particular, was used to working with deadlines in their courses, which caused delays in some assets since we weren’t clear enough about task priorities.

I believe we should have set deadlines for tasks that were not completed in the previous sprint to ensure the project did not fall too far behind. As project leaders, we did not manage task priorities and the long-term project planning well enough. In my opinion, we could have done better with a bit more discipline.

3.2.2 Conceptualization: A Missing Role in the Project

From a concept art perspective, we really struggled. We didn’t have a Concept Artist on the team, and the Game Art team needed concept art to create their assets. We decided to research reference games to help guide them, but at times, our communication wasn’t as effective as it could have been, leading to some delays. In hindsight, we could have worked more closely with the Game Art team to refine the references or given them more freedom to conduct their own research while we focused on other tasks.

From a narrative standpoint, we also spent a lot of time trying to create a story. Despite our brainstorming sessions, some aspects of the game design remained very unclear. We could have compensated for this lack of conceptualization and creative ideas by using AI much more. In fact, it was through concept art generated by ChatGPT that we eventually found ideas. I also think we could have sought more help from experts and professors who were supervising the project.

Concept art for the game generated using ChatGPT.

3.2.3 Tasks Distribution

The Games Programming team had many roles to fulfill in the project. On paper, we distributed the roles well, but in practice, some people ended up taking on significantly more tasks than others and working on almost every aspect of the game.

One of the reasons for this was that we all started programming at the beginning of the project, and once the code was nearly finished, only creative and design tasks remained. Some programmers struggled to stay motivated to work on design aspects since their profiles were more technical. This resulted in a few programmers having to take on a much heavier workload. I think we should have anticipated this possibility and reserved more coding tasks for the more technical members of the team.

With the Game Art team, we encountered difficulties in implementing assets. At the start of the project, the Game Art team didn’t have Perforce installed, meaning they couldn’t integrate their assets into the game. As a result, the programmers had to do it. Naturally, it was difficult for us to understand how the assets and their materials worked and how to restore their original colors. This workflow was far from ideal. Over the last few months we’ve fixed this, and it’s now the artists who put their assets into Unreal. We should have asked the artists to do it earlier.

With the Audio team, the main issue was mixing. The Audio students worked on Macs with limited memory. The entire class was unable to install Unreal or run the project. While this wasn’t a problem for sound creation, implementation had to be handled by a Game Programmer.

To properly mix the game, it is essential to connect the Unreal editor to Wwise to debug issues and adjust sound volumes in real time. This meant that we had to organize mixing sessions between the Programmers and the Audio team. Since I was the only one with Wwise and Unreal installed on my computer, I took on this responsibility. However, I was already overwhelmed with other tasks that other programmers were unable to take on. This was a period where I found myself overloaded, and we could have done a better job of distributing tasks.

4. What I’ll Do Differently

First, I would conduct student reviews from the very beginning of the project. We realized that meeting in person to brainstorm, review each other’s work, and ask questions significantly helped move the project forward. It created a strong team cohesion and a pleasant sense of progress.

Next, I would not hesitate to use AI much more as a tool for conceptualization, design, and narrative creation. The use of AI is still somewhat taboo, which made us hesitant to rely on it. However, when looking at the benefits it brought to our project, it’s clear that it helped us push the game further. I believe we should fully embrace this new opportunity to increase our productivity. Moreover, I see no shame in using AI to fill gaps in areas where we lack expertise rather than trying to perform tasks we are not trained for.

Another thing I would do differently is to ask for much more help from teachers and industry professionals. Of course, the goal of the project is to learn how to be independent, but as Nicolas Vallée told me toward the end of the project: “Asking teachers for help is also a way of seeking out information on your own.”

Finally, from a more technical standpoint, I would not rely as much on Blueprints as we did for this project. We came to understand the limitations of Blueprints for large-scale projects. By the end, our files looked like spaghetti bowls. Additionally, many of our system’s logic would have been easier to develop in C++ rather than Blueprints, especially when dealing with math or complex algorithms.

5. Conclusion

This project was an intense experience, but also a very exciting and rewarding one. I loved working as part of a team with people whose expertise was different from my own, and this enabled me to learn an enormous amount about the methods and approaches specific to each field.

The teamwork involved in this project confirmed to me that it’s extremely difficult to create a game on your own. Making a game is a truly collective effort, where collaboration between different professions is essential. I don’t regret the way we worked: although we didn’t get everything right, we managed to maintain a good working relationship and come up with a project I’m proud of.

Beyond teamwork, this project was also a major technical learning experience. I’ve learnt an enormous amount, particularly about development with Unreal Engine 5 and more specifically about Graphics Programming. Designing the game’s cel shader has given me a deeper understanding of graphics rendering and lighting, and I’m also very pleased with the VFX I’ve been able to create.

I’ve come away from this experience enriched, happy and with a perspective that will be very useful for my future projects. But above all, this project has confirmed that it’s this collaboration between different professions that drives me to become a video game developer.

Screenshot of our game on the school deliverable date.