My implementation of the raytracing in one weekend using CUDA.

Computer Graphics Raytracing C++ CUDA

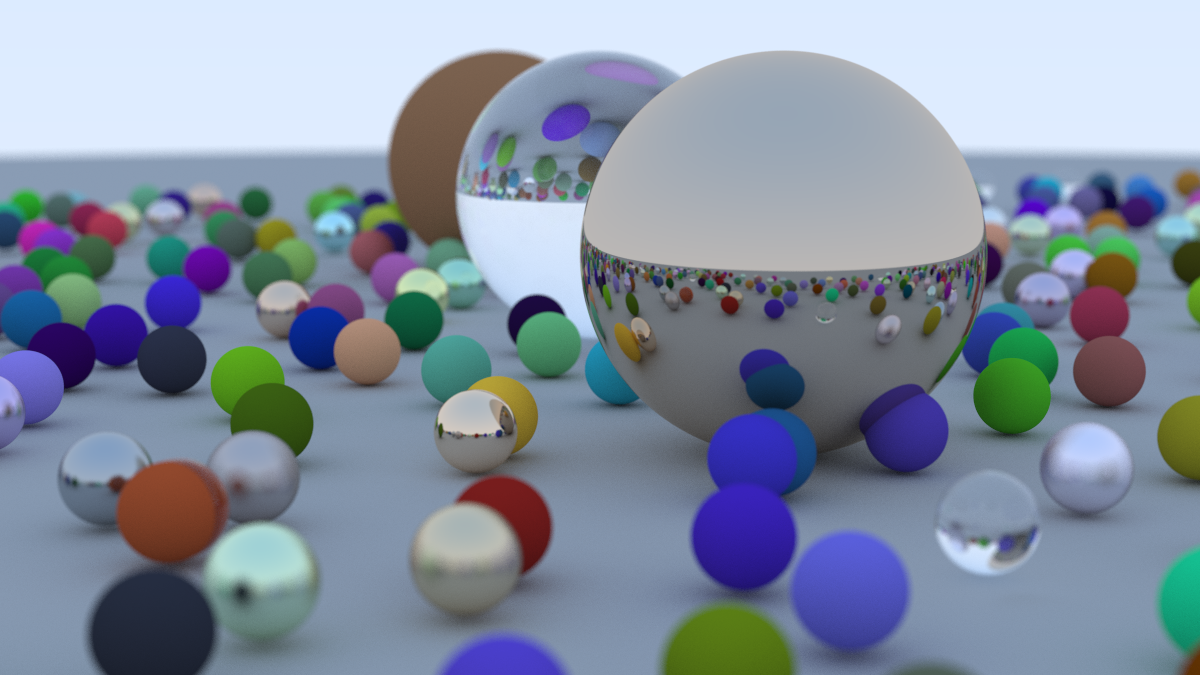

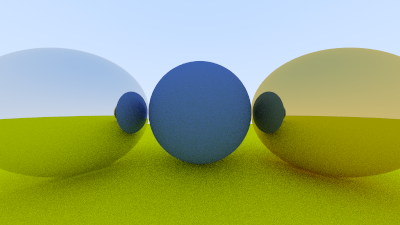

Hello, I recently took one of my weekends to implement a raytracer following the ebook Ray Tracing in One Weekend by Peter Shirley. I’d heard a lot about this book and as a computer graphics enthusiast, I had to read it. I ended up with a result similar to the book, which took 1h50 to render, given that the image is 1200x675 pixels, the number of sample pixels is 500 and the maximum number of ray bounces is 50, giving us a maximum number of possible iterations of: 1200x675x500x50 = 20’250’000’000.

My final render.

The book’s raytracer is designed to be simple and accessible to as many people as possible, so rendering is done naively on the CPU. I had a strong desire to read the other books in this series, but I thought it was a pity not to use the GPU to work more closely with modern raytracers on the market. So I remembered hearing about NVIDIA’s CUDA API, which is an API for writing parallel computing code on the GPU in C++. I’d never used CUDA before and thought this project would be perfect for that.

The first thing I did was to read Mark Harris’ technial post: An Even Easier Introduction to CUDA to get the basics down. After reading this post I saw another post by Roger Allen talking about accelerating the raytracing in one weekend rendering time using CUDA: Accelerated Ray Tracing in One Weekend in CUDA. So I used my code from my reading of the raytracing book and the CUDA post to implement my version of raytracing in one weekend in CUDA.

In this technical post I’m going to talk about the particularities I had to take into account when using CUDA in my project and my journey to get to the final result of the raytracing book. I’m not going to explain how raytracing works, as Peter Shirley’s ebook will inevitably do that better than I can. Nor do I claim to have found all the solutions to my CUDA-related problems on my own, since I’ve drawn heavily on the CUDA post. I will often reference chapters from the book so it may be beneficial to have read it.

Content

Render the first image

So we want to separate the calculation of pixel values from the writing of these values to the image. We want to do all the calculations in parallel on the GPU, because that’s what it’s designed for. We then want to use our CPU to transcribe everything into the PPM image.

But first of all, it’s important to define a macro that we’ll use for each CUDA API function call to check the error codes of the functions to help us in our development.

#define CHECK_CUDA_ERRORS(val) check_cuda((val), #val, __FILE__, __LINE__)

void check_cuda(cudaError_t result, char const* const func,

const char* const file, int const line) {

if (result) {

std::cerr << "CUDA error = " << static_cast<unsigned int>(result) << " at "

<< file << ":" << line << " '" << func << "' \n";

// Make sure we call CUDA Device Reset before exiting

cudaDeviceReset();

std::exit(99);

}

}The first thing to do is to create a buffer whose memory is shared between the CPU and GPU. To do this, we allocate a framebuffer of size image_width * image_height on the unified memory by calling cudaMallocManaged(). Unified memory is shared both by the GPU, which writes pixel values to it, and by the CPU, which reads and renders them in the PPM image.

// FrameBuffer

constexpr int kImageWidth = 400;

constexpr int kImageHeight = 225;

constexpr int kNumPixels = kImageWidth * kImageHeight;

constexpr std::size_t kFbSize = 3 * sizeof(float) * kNumPixels;

// Allocate FB

float* fb = nullptr;

CHECK_CUDA_ERRORS(cudaMallocManaged(reinterpret_cast<void**>(&fb), kFbSize));Then we need to define how many thread and blocks from our GPU we will use. Personally I simply followed the post from Roger Allen which define 8x8 thread for 2 reasons:

- A small block size should help each pixel do a similar amount of work. If some pixels work much longer than other pixels in a block, the efficiency of that block is impacted.

- A block size which has a pixel count that is a multiple of 32 enables to fit into warps evenly.

I also added a timer like in the cuda post to measure the GPU initialization + calculation time.

constexpr int kTx = 8;

constexpr int kTy = 8;

const std::clock_t start = clock();

// Render our buffer

dim3 blocks(kImageWidth / kTx + 1, kImageHeight / kTy + 1);

dim3 threads(kTx, kTy);

Render<<<blocks, threads>>>(fb, kImageWidth, kImageHeight); // I'll show the function right after.

CHECK_CUDA_ERRORS(cudaGetLastError());

CHECK_CUDA_ERRORS(cudaDeviceSynchronize());

const std::clock_t stop = clock();

const double timer_seconds = static_cast<double>(stop - start) / CLOCKS_PER_SEC;

std::cerr << "took " << timer_seconds << " seconds.\n";Now we need a Render() function that runs on the GPU to calculates the value of each pixel and write it into the framebuffer but is called by the CPU. Such a function is called a kernel in CUDA. To tell the cuda compiler that a function is a kernel we need to add the global keyword to it:

__global__ void Render(float *fb, const int image_width, const int image_height) {

const int i = threadIdx.x + blockIdx.x * blockDim.x;

const int j = threadIdx.y + blockIdx.y * blockDim.y;

if((i >= max_x) || (j >= max_y))

return;

const int pixel_index = j * image_width * 3 + i * 3;

fb[pixel_index + 0] = static_cast<float>(i) / image_width;

fb[pixel_index + 1] = static_cast<float>(j) / image_height;

fb[pixel_index + 2] = 0.2;

}Note that we use the CUDA built-in variables threadIdx and blockIdx to identify the coordinates of each thread in the image (i,j) so that we know how to calculate the final color. It’s possible that images whose size is not a multiple of the block size contain additional threads running outside the image. We need to ensure that these threads don’t try to write to the image buffer and return prematurely.

After executing the kernel function, we can read the pixel values from the processor and write them to the image file as in the book, and simply release the frame buffer memory once we’re done. (I’ve put all the thread creation code in here to be self-explanatory) :

constexpr int kTx = 8;

constexpr int kTy = 8;

const std::clock_t start = clock();

// Render our buffer

dim3 blocks(kImageWidth / kTx + 1, kImageHeight / kTy + 1);

dim3 threads(kTx, kTy);

// I'll show the function right after.

Render<<<blocks, threads>>>(fb, kImageWidth, kImageHeight);

CHECK_CUDA_ERRORS(cudaGetLastError());

CHECK_CUDA_ERRORS(cudaDeviceSynchronize());

const std::clock_t stop = clock();

const double timer_seconds = static_cast<double>(stop - start) / CLOCKS_PER_SEC;

std::cerr << "took " << timer_seconds << " seconds.\n";

// Output FB as Image

std::cout << "P3\n" << nx << " " << ny << "\n255\n";

for (int j = kImageHeight-1; j >= 0; j--) {

for (int i = 0; i < kImageWidth; i++) {

const size_t pixel_index = j * 3 * kImageWidth + i * 3;

const float r = fb[pixel_index + 0];

const float g = fb[pixel_index + 1];

const float b = fb[pixel_index + 2];

const int ir = int(255.99*r);

const int ig = int(255.99*g);

const int ib = int(255.99*b);

std::cout << ir << " " << ig << " " << ib << "\n";

}

}

checkCudaErrors(cudaFree(fb));If we open the ppm file (I use ppm viewer site personally) we should have the first image of the raytracing book:

The first PPM image of the book.

Create classes that can be used on both the CPU and GPU

The second tricky thing to do after writing to a framebuffer was to be able to use common classes such as the Vec3 class or the Ray class on both the CPU and GPU.

To do this, we simply need to tell the compiler that every method in these classes can be called from the host (CPU code) and from the device (GPU code) using the host and device keywords on all methods (this includes constructors and operators).

Here is some small examples with some methods of my Vec3 class:

template<typename T>

class Vec3 {

public:

__host__ __device__ constexpr Vec3<T>() noexcept = default;

__host__ __device__ constexpr Vec3<T>(const T x, const T y, const T z) noexcept

: x(x),

y(y),

z(z) {}

...

__host__ __device__ [[nodiscard]] constexpr Vec3<T> operator+(

const Vec3<T>& v) const noexcept {

return Vec3<T>(x + v.x, y + v.y, z + v.z);

}

...

__host__ __device__ [[nodiscard]] constexpr T DotProduct(

const Vec3<T>& v) const noexcept {

return x * v.x + y * v.y + z * v.z;

}

...

}This class is a template one to be able to easily switch between float and double if I want to but you need to be aware that the current GPUs run fastest when they do calculations in single precision. Double precision calculations can be several times slower on some GPUs. That’s why in all my program I will only use Vec3F:

using Vec3F = Vec3<float>;The advantage of my template class is that I can easily use the same class in a raytracing that will run on the CPU with double precision for more precise result.

First rays

Functions for calculating rays, intersections etc will be 100% used by our GPU. The whole point of using CUDA is to run all these calculation functions on GPU threads, which is why we need to annotate all these functions with the device keyword, like the CalculatePixelColor function (the color() function from the book) for example:

__device__ Vec3F CalculatePixelColor(const RayF& r) {

Vec3F unit_direction = r.direction().Normalized();

float t = 0.5f*(unit_direction.y + 1.0f);

return (1.0f - t) * Vec3F(1.0, 1.0, 1.0) + t * Vec3F(0.5f, 0.7f, 1.0f);

}Thanks to the device keyword this function can be executed by the kernel:

__global__ void Render(Vec3F *fb, int image_width, int image_height,

Vec3F pixel_00_loc, Vec3F pixel_delta_u, Vec3F pixel_delta_v,

Vec3F camera_center) {

const int i = threadIdx.x + blockIdx.x * blockDim.x;

const int j = threadIdx.y + blockIdx.y * blockDim.y;

if ((i >= image_width) || (j >= image_height))

return;

const int pixel_index = j * image_width + i;

const auto pixel_center = pixel_00_loc + (i * pixel_delta_u) +

(j * pixel_delta_v);

const auto ray_direction = pixel_center - camera_center;

const RayF r(camera_center, ray_direction);

fb[pixel_index] = CalculatePixelColor(r);

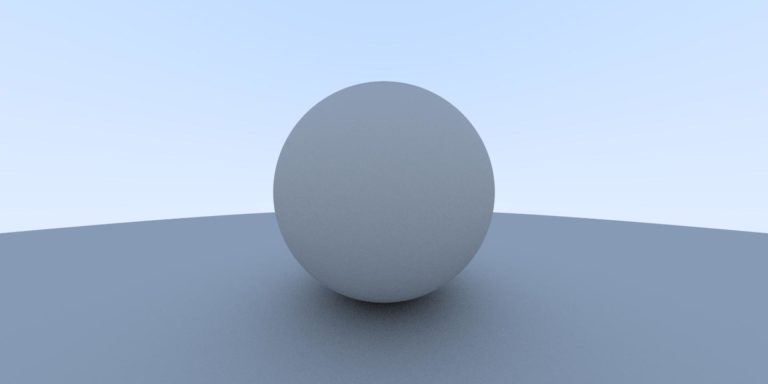

}There are some changes in the viewport calculations between the book and the post cuda. I personally kept the book calculations and ended up with my background reversed in y:

The blue gradient image reversed.

To resolve this slight problem I simply inverted my loop j when I write in the image:

// The j loop is inverted compared to the raytracing in a weekend book because

// the Render function executed on the GPU has an inverted Y.

for (int j = 0; j < kImageHeight; j++) {

for (int i = 0; i < kImageWidth; i++) {

const size_t pixel_index = j * kImageWidth + i;

write_color(std::cout, fb[pixel_index]);

}

}Now the image is correct:

The blue gradient image.

Hit sphere

Displaying a sphere is quite simple to do, especially since no GPU allocation is necessary in this chapter of the book. You just have to be careful to put the device keyword on all new functions that will be executed via the kernel. Once CUDA is setup correctly and the allocations are made, this type of code poses no difficulty during development, it is one of the strong points of CUDA.

First sphere drawn.

World creation

The previous chapter was very simple to adapt to CUDA code, however this one will be much more complex. We enter the chapters of abstraction of the different “Hittable” objects and the creation of the world.

All our objects and our world must be allocated on the GPU, the CPU does not need to access them. They must therefore be device usable and must be allocated via the cudaMalloc() function. We store hittables in pointers that act as vector<shared_ptr> like in the book:

...

__global__ void CreateWorld(Hittable** d_list, Hittable** d_world) {

if (threadIdx.x == 0 && blockIdx.x == 0) {

*d_list = new Sphere(Vec3F{0, 0, -1}, 0.5f);

*(d_list + 1) = new Sphere(Vec3F(0, -100.5, -1), 100);

*d_world = new HittableList(d_list, 2);

}

}

__global__ void FreeWorld(Hittable** d_list, Hittable** d_world) {

if (threadIdx.x == 0 && blockIdx.x == 0) {

if (*d_world) {

delete *d_world;

*d_world = nullptr;

}

if (*d_list) {

delete *d_list;

*d_list = nullptr;

}

if (*(d_list + 1)) {

delete *(d_list + 1);

*(d_list + 1) = nullptr;

}

}

}

...

int main() {

...

// Allocate the world on the GPU.

Hittable** d_list;

CHECK_CUDA_ERRORS(cudaMalloc(reinterpret_cast<void**>(&d_list), 2 * sizeof(Hittable*)));

Hittable** d_world;

CHECK_CUDA_ERRORS(cudaMalloc(reinterpret_cast<void**>(&d_world), sizeof(Hittable*)));

CreateWorld<<<1, 1>>>(d_list, d_world);

CHECK_CUDA_ERRORS(cudaGetLastError());

CHECK_CUDA_ERRORS(cudaDeviceSynchronize());

...

}

Note that CreateWorld and FreeWorld are global to be able to call them from the host code even if the device will execute them.

Then we can free all the memory of the program and reset the CUDA device before exiting the main process:

// clean up

FreeWorld<<<1, 1>>>(d_list, d_world);

CHECK_CUDA_ERRORS(cudaGetLastError());

CHECK_CUDA_ERRORS(cudaDeviceSynchronize());

CHECK_CUDA_ERRORS(cudaFree(d_rand_state));

CHECK_CUDA_ERRORS(cudaFree(d_world));

CHECK_CUDA_ERRORS(cudaFree(d_list));

CHECK_CUDA_ERRORS(cudaFree(fb));

// Useful for cuda-memcheck --leak-check full

CHECK_CUDA_ERRORS(cudaDeviceReset());

return EXIT_SUCCESS;Now we have a sphere and a ground both allocated on the GPU and the image looks like that:

Resulting render using the world architecture.

Camera class

The chapter on the camera is also an important passage of code factorization. I made sure that my camera is host and device usable because I think that we can want to instantiate the camera in the host code while using it in the device code although personally I instantiate it in the device code but I will talk about it later.

I also took advantage of the 100% static behavior of the program and the advantages of C++ to store most of the camera attributes as a constant evaluated at compile time via the keyword “constexpr”.

class Camera {

...

static constexpr float kAspectRatio = 16.f / 9.f;

static constexpr int kImageWidth = 400;

static constexpr int kImageHeight = static_cast<int>(kImageWidth / kAspectRatio);

// My Vec3F class is undefined in the device code when used as constexpr and I don't

// know why so it is not constexpr for the moment.

Vec3F kLookFrom = Vec3F(0, 0, 0);

// Calculate the horizontal and vertical delta vectors from pixel to pixel.

Vec3F pixel_delta_u{}; // Offset to pixel to the right

Vec3F pixel_delta_v{}; // Offset to pixel below

Vec3F pixel_00_loc{};

}If you read the comments you understood that I had a problem with the Vec3F kLookFrom attribute. Indeed in the code of my Render function I can access all my constants except kLookFrom. I concluded that my Vec3F class (which nevertheless has a constexpr constructor) was not compatible with CUDA in compile time either because it is a user-type or because of the template aspect. I haven’t found any info that would support the theory that CUDA only understands basic C++ types in compile time so I’ll classify this theory as speculation.

The pixel_delta_u, pixel_delta_v and pixel_00_loc attributes can also be known in compile time but I found that there were too many intermediate values to store to calculate their final result. I consider it better to calculate their values in the Initialize() function via intermediate values in “constexpr” than to store everything in my camera class:

__host__ __device__ void Initialize() noexcept {

// Determine viewport dimensions.

constexpr float kFocalLength = 1.f;

constexpr float kViewportHeight = 2.f;

constexpr float kViewportWidth =

kViewportHeight * (static_cast<float>(kImageWidth) / kImageHeight);

// Calculate the vectors across the horizontal and down the vertical

// viewport edges.

constexpr auto kViewportU = Vec3F(kViewportWidth, 0, 0);

constexpr auto kViewportV = Vec3F(0, -kViewportHeight, 0);

// Calculate the horizontal and vertical delta vectors from pixel to pixel.

pixel_delta_u = kViewportU / kImageWidth; // Offset to pixel to the right

pixel_delta_v = kViewportV / kImageHeight; // Offset to pixel below

// Calculate the location of the upper left pixel.

const auto kViewportUpperLeft = kLookFrom -

Vec3F(0, 0, kFocalLength) -

kViewportU / 2 - kViewportV / 2;

pixel_00_loc = kViewportUpperLeft + 0.5 * (pixel_delta_u + pixel_delta_v);

}Now all that remains is to create the camera by allocating it on the GPU memory because it is the device code that will use it without forgetting to deallocate everything at the end of the program (I only show the allocation because deallocation follows a similar pattern)

...

__global__ void CreateWorld(Camera** d_camera, Hittable** d_list, Hittable** d_world) {

if (threadIdx.x == 0 && blockIdx.x == 0) {

*d_list = new Sphere(Vec3F{0, 0, -1}, 0.5f);

*(d_list + 1) = new Sphere(Vec3F(0, -100.5, -1), 100);

*d_world = new HittableList(d_list, 2);

*d_camera = new Camera();

(*d_camera)->Initialize();

}

}

// Also updated FreeWorld().

...

int main() {

...

// Allocate the camera on the GPU.

Camera** d_camera = nullptr;

CHECK_CUDA_ERRORS(

cudaMalloc(reinterpret_cast<void**>(&d_camera), sizeof(Camera*)));

...

// Don't forget to call cudaFree().

}Now we have the exact same image but the code is cleaner:

Same result using the camera class.

Random numbers with CUDA for the Anti-Aliasing

The chapter 8 is about anti-aliasing which consist of sampling the square region centered at a pixel that extends halfway to each of the four neighboring pixels. To sample the square pixel we will take some random point inside it. So we need to generate random numbers via the CUDA API to acces them on the GPU. To do so we need to use the cuRAND library. Also since random numbers on a computer actually consist of pseudorandom sequences, we need to setup and remember state for every thread on the GPU. That’s why we will create a “curandState” per pixel:

#include <curand_kernel.h>

...

int main() {

...

curandState* d_rand_state;

CHECK_CUDA_ERRORS(cudaMalloc(reinterpret_cast<void**>(&d_rand_state),

kNumPixels * sizeof(curandState)));

...

}Then we need to initialize the curandState object per pixel for every thread. The CUDA post has an approach which consits in creating a second kernel to be able to separate the time for random initialization from the time it takes to do the rendering, in order to measure the only the rendering. I followed the same principle but you can do it in the Render() kernel if you want to.

__global__ void RenderInit(curandState* rand_state) {

const int i = threadIdx.x + blockIdx.x * blockDim.x;

const int j = threadIdx.y + blockIdx.y * blockDim.y;

if ((i >= Camera::kImageWidth) || (j >= Camera::kImageHeight))

return;

const int pixel_index = j * Camera::kImageWidth + i;

// Each thread gets same seed, a different sequence number, no offset

curand_init(1984, pixel_index, 0, &rand_state[pixel_index]);

}We can finally use it in the Render() kernel by making a local copy of the current “curandState” object to which we call curand_uniform():

__global__ void Render(Vec3F* fb, Camera** camera, Hittable** world,

const curandState* rand_state) {

const int i = threadIdx.x + blockIdx.x * blockDim.x;

const int j = threadIdx.y + blockIdx.y * blockDim.y;

if ((i >= Camera::kImageWidth) || (j >= Camera::kImageHeight))

return;

const int pixel_index = j * Camera::kImageWidth + i;

curandState local_rand_state = rand_state[pixel_index];

Vec3F col(0, 0, 0);

for (int s = 0; s < Camera::kSamplesPerPixel; s++) {

const auto offset = Vec3F(curand_uniform(&local_rand_state) - 0.5f,

curand_uniform(&local_rand_state) - 0.5f, 0.f);

const auto pixel_sample = (*camera)->pixel_00_loc +

((i + offset.x) * (*camera)->pixel_delta_u) +

((j + offset.y) * (*camera)->pixel_delta_v);

const auto ray_direction = pixel_sample - (*camera)->kLookFrom;

const RayF r((*camera)->kLookFrom, ray_direction);

col += Camera::CalculatePixelColor(r, world);

}

fb[pixel_index] = col / Camera::kSamplesPerPixel;

}This give us this result which is the same image but using anti-aliasing:

Same render but with anti-alisaing.

Avoid recursion when rays bounce.

The next chapter introduces the first material type we apply to our sphere which is the diffuse material also called matte. Light that reflects off a diffuse surface has its direction randomized but it might also be absorbed rather than reflected. The darker the surface the more the light is absorbed.

The first implementation of reflected rays on diffuse surfaces is quite naive and reflects the rays in a totally random direction using a rejection method to generate a correct random vector. It also ommits the fact that the function is recursive and can call itself a sufficient number of times to cause a stackoverflow in our CUDA code context. That’s why I followed the adivce from the CUDA post and decided to already put a max ray bounce limit in the CalculatePixelColor() device function:

__device__ [[nodiscard]] static Color CalculatePixelColor(

const RayF& r, Hittable** world, curandState* local_rand_state) noexcept {

RayF cur_ray = r;

float cur_attenuation = 1.f;

for (int i = 0; i < kMaxBounceCount; i++) {

const HitResult hit_result =

(*world)->DetectHit(cur_ray, IntervalF(0.f, math_utility::kInfinity));

if (hit_result.has_hit) {

const auto direction =

GetRandVecOnHemisphere(local_rand_state, hit_result.normal);

cur_attenuation *= 0.5f;

cur_ray = RayF{hit_result.point, direction};

}

else

{

const Vec3F unit_direction = cur_ray.direction().Normalized();

const float a = 0.5f * (unit_direction.y + 1.f);

const auto color =

(1.f - a) * Color(1.f, 1.f, 1.f) + a * Color(0.5f, 0.7f, 1.f);

return cur_attenuation * color;

}

}

return Vec3F{0.f, 0.f, 0.f}; // exceeded recursion.

}We also need to be careful about how we write the new random vector generation functions. In addition to having to pass our local_rand_state object from the Render() kernel as a parameter, we also have to take into account the fact that the curand_uniform() function returns a value between 0 and 1. But when we want to generate a random vector in the unit sphere, we want it to be between -1 and 1. This is why we use a little mathematical trick by multiplying the result of curand_uniform() by 2 and then subtracting 1 to go from [0; 1] to [-1; 1].

Here is my device_random.h file to generate correct random vectors on the GPU:

#pragma once

#include "vec3.h"

#include <curand_kernel.h>

__device__ [[nodiscard]] inline Vec3F GetRandomVector(

curandState* local_rand_state) noexcept {

return Vec3F{curand_uniform(local_rand_state),

curand_uniform(local_rand_state),

curand_uniform(local_rand_state)};

}

__device__ [[nodiscard]] inline Vec3F GetRandVecInUnitSphere(

curandState* local_rand_state) noexcept {

Vec3F p{};

do {

// Transform random value in range [0 ; 1] to range [-1 ; 1].

p = 2.0f * GetRandomVector(local_rand_state) - Vec3F(1, 1, 1);

} while (p.LengthSquared() >= 1.0f);

return p;

}

__device__ [[nodiscard]] inline Vec3F GetRandVecOnHemisphere(

curandState* local_rand_state, const Vec3F& hit_normal) noexcept {

const Vec3F on_unit_sphere = GetRandVecInUnitSphere(local_rand_state).Normalized();

if (on_unit_sphere.DotProduct(hit_normal) > 0.f) // In the same hemisphere as the normal

return on_unit_sphere;

return -on_unit_sphere;

}Now we can create our first diffuse surface render:

First diffuse surface render.

The material abstraction.

The next chapter introduces an abstract class to represent materials. This class would be used by the device code so you already know which keyword we should use on the methods. Also note that the materials need to generate random vectors in the Scatter method, that’s why we need to add the local_rand_state object as parameter in the method:

class Material {

public:

__device__ constexpr Material() noexcept = default;

__device__ Material(Material&& other) noexcept = default;

__device__ Material& operator=(Material&& other) noexcept = default;

__device__ Material(const Material& other) noexcept = default;

__device__ Material& operator=(const Material& other) noexcept = default;

__device__ virtual ~Material() noexcept = default;

__device__ virtual bool Scatter(const RayF& r_in, const HitResult& hit,

Color& attenuation, RayF& scattered,

curandState* local_rand_state) const = 0;

};The next change from the book is that we cannot store shared pointer Material in the HitResult struct because the base CUDA C++ language does not provide standard library support. Their are some 3rd parties that have created their own implementations but I’d like to stick to the book’s vision of having no dependencies in the code (expect CUDA for this project). So we will just store the material as a raw pointer.

Then after creating the Lambertian and the Metal materials, we can add these to some sphere and see the result. We just need to change our way to create our spheres and to destroy them. Becuase we store the sphere in a hittable* list, we should normally dynamic_cast each hittable to sphere in order to delete their material. But dynmaic_cast is not allowed in device code, that’s why I simply use a static_cast even if it is a huge code smell. The goal is to write the code in one weekend so I don’t have time to create a better architecture for my code sorry.

Here is the two horrible functions:

__global__ void CreateWorld(Camera** d_camera, Hittable** d_list, Hittable** d_world) {

if (threadIdx.x == 0 && blockIdx.x == 0) {

d_list[0] = new Sphere(Vec3F(0.f, -100.5f, -1.f), 100.f,

new Lambertian(Color(0.8f, 0.8f, 0.0f)));

d_list[1] = new Sphere(Vec3F(0.f, 0.f, -1.2f), 0.5f,

new Lambertian(Color(0.1f, 0.2f, 0.5f)));

d_list[2] = new Sphere(Vec3F(-1.f, 0.f, -1.f), 0.5f,

new Metal(Color(0.8f, 0.8f, 0.8f)));

d_list[3] = new Sphere(Vec3F(1.f, 0.f, -1.f), 0.5f,

new Metal(Color(0.8f, 0.6f, 0.2f)));

*d_world = new HittableList(d_list, 4);

*d_camera = new Camera();

(*d_camera)->Initialize();

}

}

__global__ void FreeWorld(Camera** d_camera, Hittable** d_list, Hittable** d_world) {

if (threadIdx.x == 0 && blockIdx.x == 0) {

if (*d_camera)

{

delete *d_camera;

d_camera = nullptr;

}

if (*d_world) {

delete *d_world;

*d_world = nullptr; // Set the pointer to nullptr after deletion

}

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

// Dynamic_cast is not allowed in device code so we use static_cast and yes I

// know that is a real code smell here but the objective is to write the code

// in a weekend so I don't want to search for a better architecture now.

delete static_cast<Sphere*>(d_list[i])->material;

delete d_list[i];

}

}

}And here is the result:

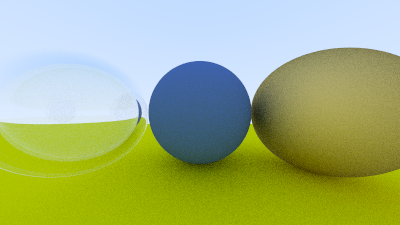

Spheres with different materials.

Then it’s time to implement the Dielectric material. There is no special CUDA code here so let’s jump to the image result:

Render with two dielectric material on the left.

Final result

Let me jump to the final result because the last two chapters concerned the customization of the camera and the addition of a defocus blur, but the code does not really change compared to the code in the book.

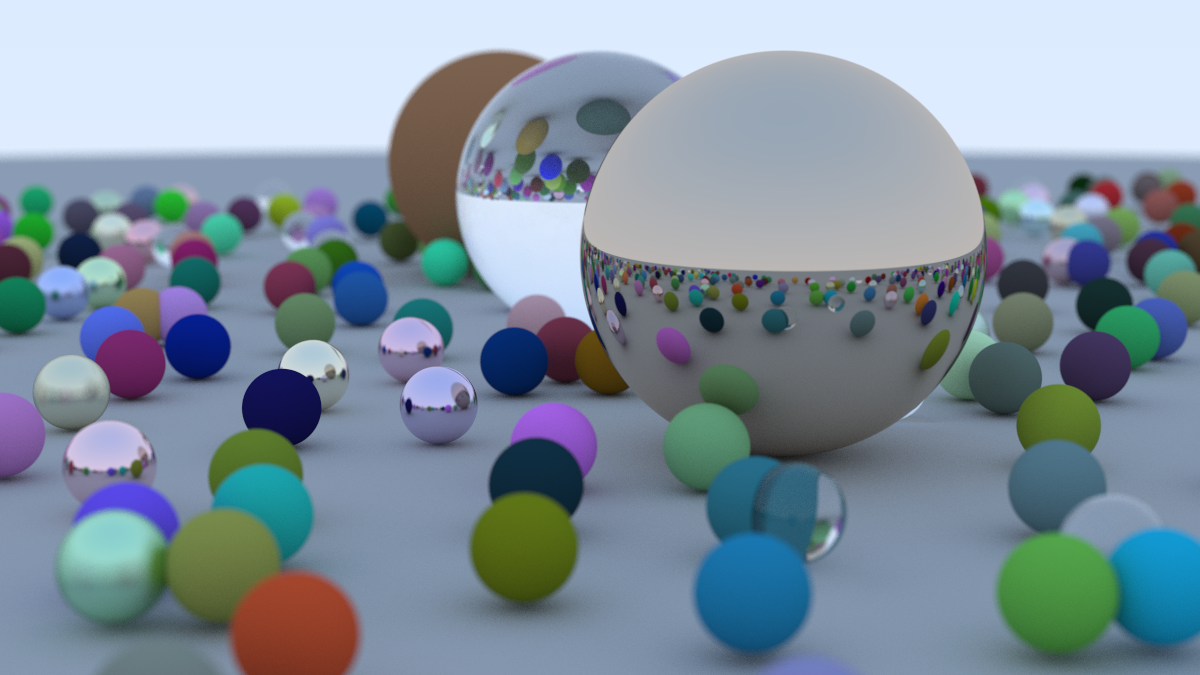

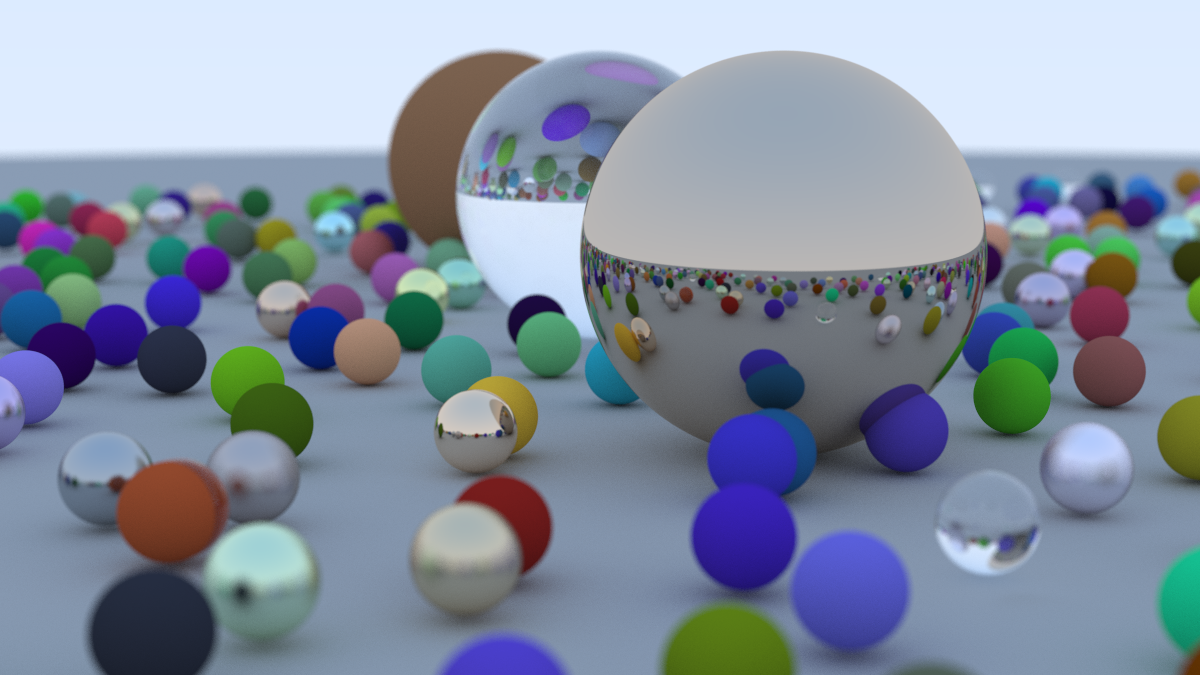

To get the final result, simply create a large number of spheres randomly, change the size of the image to 1200x675, set the number of sample pixels to 500 and the maximum bounce per radius to 50. This give us this result:

Final result.

The book’s implementation using only the CPU took 1h50 to render the image using my Intel Core i7 CPU while my implementation with CUDA using 8x8 threads took 20min35s using my NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3050Ti GPU. I also took the liberty of testing some thread values to try to get a better result and I got the best performance using 16x16 thread for a calculation time of 16min15s. This makes the implementation with CUDA almost 7x faster

Conclusion

Going from 1h50 with my Intel Core i7 CPU to 16min15s with my NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3050Ti GPU is a huge change. It wasn’t easy to use the CUDA API at first but once you wrote a few pieces of code, you got used to it quite well.

Overall, I find using CUDA quite simple for a small project like this. I also find the ratio of effort provided - efficiency obtained very good. I definitely want to continue reading the series of books on raytracing using CUDA but also to use CUDA in other contexts like AI for example.

Thank you for reading this technical post. Don’t hesitate to check out the project code on my github